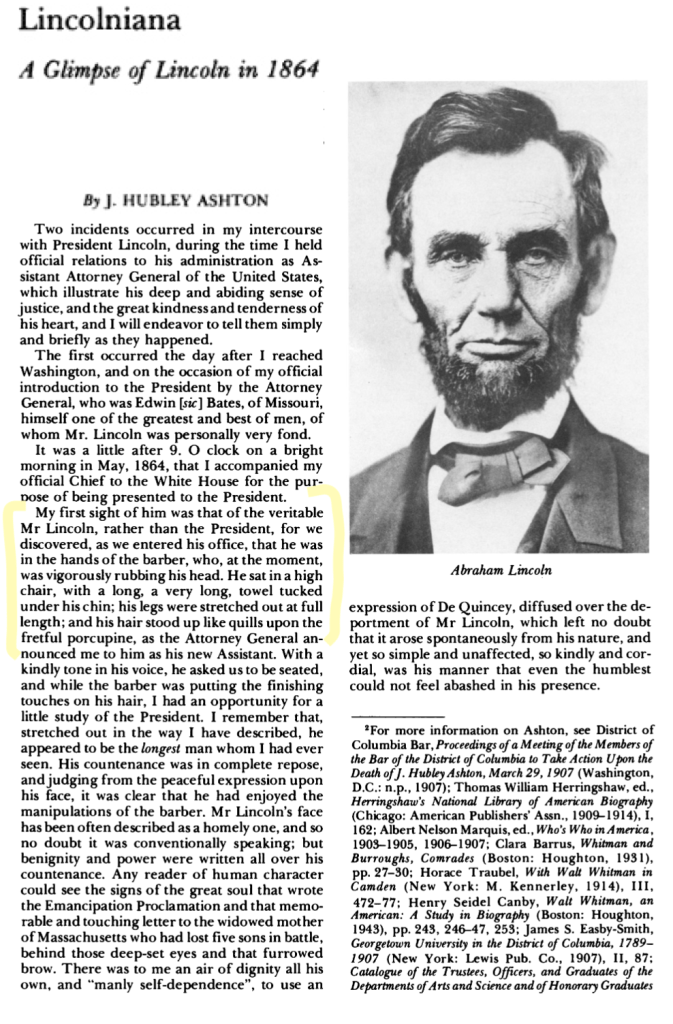

My great-grandfather, Joseph Hubley Ashton, was a 19th-century lawyer and a powerful voice for birthright citizenship as a pillar of United States immigration policy. He was also an admirer of Abraham Lincoln and a friend of Walt Whitman, but I knew nothing about him until I learned about a family treasure inherited by my mother — his account of a highly informal meeting with President Lincoln. As a young Assistant Attorney General during the Civil War, Ashton was taken by the Attorney General to be introduced to the Commander-in-Chief. During their meeting, the president was “in the hands of the barber… his legs were stretched out at full length, and his hair stood up like quills upon the fretful porcupine.” The text, an endearing account of the Great Emancipator at ease and enjoying the company of fellow-lawyers, was published in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Vol. 69, No. 1, Feb., 1976) and is posted here and at left/above.

The Lincoln anecdote sparked my interest in this ancestor. When I learned more, I was struck by the relevance of his work to some of our own painful and divisive issues — immigration in particular, but more broadly the struggle to resist powerful contemporary tendencies toward states’ rights and white supremacy. By the 1890s, the young lawyer who revered Lincoln and the Union cause had become a fierce defender of birthright citizenship and the 14th Amendment. He argued fiercely against the swell of anti-immigrant and racist tendencies of his era, and his words have a remarkable resonance in ours. I found those words in the public record, not in family stories — apart from the Lincoln anecdote, there were none. My mother was only two years old when he died, and I never thought to ask my grandmother about her father. If I had, I might have learned about the man as well as the lawyer — at least why he was always known as “Hubley,” never Joe.

Hubley was born in Philadelphia in 1836, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, and went on to study law as it was done in those days, in the office of a local lawyer, although he took some courses at the Penn Law School. According to an obituary notice by the D.C. Bar Association, his legal education took place during the “heated discussions” of the 1850s, during which he “learned to loathe slavery and secession.” In 1857 he was admitted to the Bar in Philadelphia, and afterwards became the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. After 1864 he served the Union by representing the government in the so-called Prize Cases concerning ships captured carrying contraband or running the Union blockade of southern ports. The case of the Venice, a ship owned by an English resident of New Orleans carrying 274 bales of cotton and captured in Lake Pontchartrain by Admiral Farragut, was one of the most important of these. Ashton’s argument before the Supreme Court included a passionate defense of the right of the President to seize and search. At this stage of his career, Ashton was a forceful advocate for the powers of the executive branch.

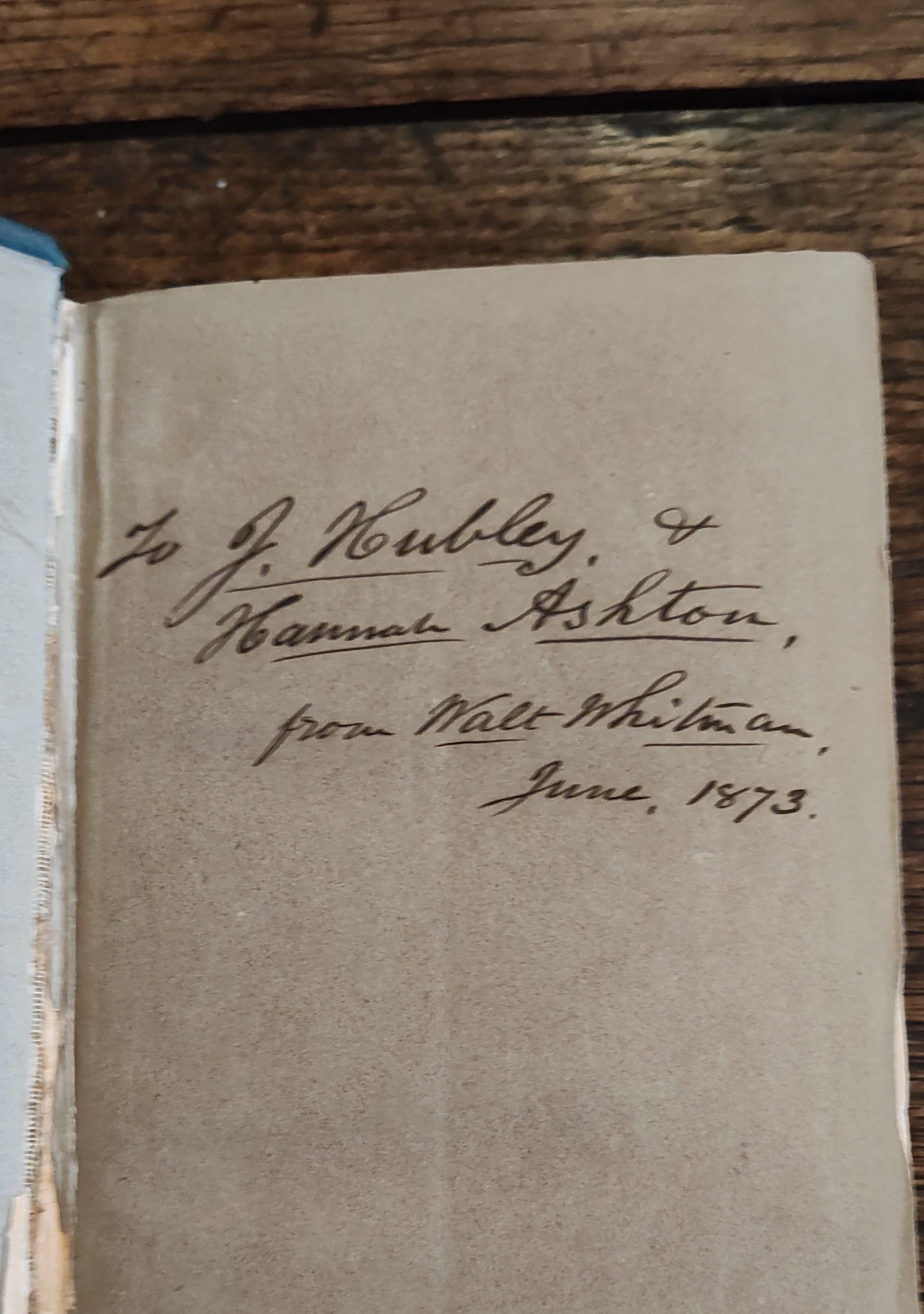

During the war Hubley made friends with Walt Whitman, who worked as a clerk in the Indian Bureau while he tended to wounded soldiers in DC hospitals. Along with my great-grandparents, J. Hubley and Hannah Ashton, Whitman was a member of the anti-slavery, pro-women’s rights circle of William Douglas O’Connor [see Notes, below], great friend and later fierce defender of the poet. An observer noted that while Whitman was at work, Hubley would often “be leaning familiarly on the desk where Walt would be writing. They were fast friends — talked a good deal together.” When the Secretary of the Interior, James Harlan, fired Whitman because he found Leaves of Grass morally offensive, Ashton made the case for his friend, emphasizing Whitman’s care for the wounded. Harlan had declared that he would “not have the author of that book in this Department… if the President of the United States should order his reinstatement, I would resign sooner than I would put him back.” Hubley could not persuade the Secretary to “put him back,” but he did talk him out of banning Whitman entirely from government employment; the poet served as a clerk in the Attorney General’s office for the rest of his time in Washington.

Ashton remained in government until 1869, through Reconstruction. He later praised the statesmen of that too-brief era and lamented the destruction, over the next decades, of so much of what they had achieved. His feelings, I imagine, were similar to the feelings of survivors of bus boycotts and beatings as they watch our courts dismantle the Voting Rights Act.

When he left government service, Hubley spent a few years teaching and helping to establish the Georgetown University Law School, then entered private practice in 1874. His wartime record with the Prize Cases had established him as an authority on international law, and much of his practice involved representation of the government in cases in which claims were made against the United States. In the hindsight of history, however, it was not Ashton’s work on behalf of the government that constituted his most significant contribution to United States law. On the contrary, his reputation rests on his representation of a claimant against the government, specifically against the infamous Chinese Exclusion Acts.

In 1882 Congress passed and President Arthur signed the first of several acts banning the immigration of Chinese laborers — the earliest restrictions placed on immigration to the United States. The Exclusion Acts were contested in their day; they were more popular in the West than the East, generally favored by organized labor and resisted — unsuccessfully — by some who profited from cheap labor as well as a few persons and groups who opposed racial exclusion on principled grounds. These flagrantly race-based statutes were not removed until 1943, when the United States was allied with China in the Second World War. In 2012 the House of Representatives issued a formal, if belated, apology.

In 1898 Wong Kim Ark, a man born in the United States to Chinese parents who had taken him back to China as a child, was denied admission to the country under the Geary Act of 1892, an extension of the initial Exclusion Act. Ashton, representing the plaintiff in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, argued on the basis of the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment that because Wong was born in the United States he was an American citizen. “Prejudice of race and pretension of caste were set aside by the 14th Amendment,” he claimed, “which ordained in unequivocal terms that ‘all persons born in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States.’ The language cannot by construction or interpretation be confined… to persons of the Caucasian race and persons of African descent, to the exclusion of persons of Mongolian descent.” Here Ashton employed the definition of birthright citizenship known as jus soli, in which citizenship is based on place of birth, as opposed to descent. The government, on the other hand, based its case on jus sanguinis, or descent by blood. It is worth noting here that descent was calculated through the father except for enslaved African people, whose children — for obvious reasons — inherited the status of their mothers. Ashton pointed out that jus sanguinis could not in any case apply to the children of enslaved people, who were not and could not be citizens.

The government argued Wong Kim Ark in explicitly racist terms, declaring that “Large numbers of Chinese laborers of a distinct race and religion residing apart by themselves… and apparently incapable of assimilation with our people, might endanger good order and be injurious to the public interests.” For these and other “persuasive reasons we have refused citizenship to Chinese subjects; and yet, as to their offspring, who are just as obnoxious, and to whom the same reasons for exclusion apply with equal force, we are told we must accept them as fellow-citizens… There certainly should be some honor and dignity in American citizenship that would be sacred from the foul and corrupting taint of a debasing alienage.” (As I write, former-president Trump continues to make disgusting remarks about immigrants “poisoning the blood” of this country.) The government argument continued with what must have seemed to some a conclusive menace: “Are Chinese children born in this country to share with the patriots of the American Revolution the exalted qualifications of being eligible to the Presidency of the nation?… surely in that case American citizenship is not worth having.”

Like the plaintiff, the government employed the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment, but placed emphasis on the phrase “not subject to any foreign power.” The Solicitor General, Holmes Conrad (a former major in the Army of the Confederacy), claimed that because Wong’s parents were “subject to the Emperor of China,” so was the son. He argued that birthright citizenship, “feudal and monarchical,” was not suited to republican government, and insisted that citizenship belonged to the states rather than the nation. Making use of the notorious Dred Scott decision, he argued that persons “who were at the time of the adoption of the Constitution recognized as citizens of the several States, became also citizens of this new political body, but none other. It was formed by them and their posterity, but for no one else.” Conrad defended states’ rights and denounced Reconstruction in the most extreme language, saying:

“The idea of citizenship of the United States, apart from citizenship of a State, was the offspring of that unhappy period of rabid rage and malevolent zeal when corrupt ignorance and debauched patriotism held high carnival in the halls of Congress, and a ‘reconstruction’ of States which had contributed largely to the construction of the United States remained an object of unremitting endeavor until the treasuries and credit of those states had become exhausted and the plunder upon that which that form of patriotism was nourished no longer remained.”

Ashton responded with similar passion. “It is true that the framers of the Constitution, unfortunately for the country, failed to perceive, and it was left for the statesmen of the reconstruction period who had carried the Government safely through the great war of the rebellion to discover, the necessity for a definition of citizenship which should free that citizenship from its disastrous entanglements with State citizenship, for which the country had paid so dearly in costly treasure and still more costly blood…” Here the experienced lawyer, now in his sixties, sounds like the young admirer of Lincoln as he defends the Union cause, Reconstruction, and — most particularly — the 14th Amendment. “We submit,” he argued, “that the 14th Amendment is a valid part of the constitution, and that it is the plain and intended meaning of that article that all persons born upon the soil and subject to the authority and laws of the United States, without distinction of color or race, and irrespective of the nationality or color, or race, or previous political condition of their parents, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

I was gratified, of course, to find my ancestor speaking so fiercely and clearly on behalf of birthright citizenship and in opposition to such a flagrant reversion to the ideology of slaveholders and secessionists. But I was astonished — almost dazed — by the entire argument and discussion, by the blatant expression in the 1890s of notions that had been “settled” by war and Reconstruction. Wong Kim Ark was argued 33 years after Appomattox. As I read the words of the Solicitor General — and even though, as Heather Cox Richardson has reminded us, the South won the Civil War — I was astounded at his breathtakingly explicit defense of states’ rights and white supremacy. (My nephew, a Virginia lawyer, gently reminds me that I live in the blue bubble of Cambridge, Mass. He is equally dismayed, but not nearly as astonished.)

It has been particularly strange, almost surreal, to read these words while hearing on the evening news about attempts by the Colorado Supreme Court and the intrepid Maine Secretary of State to enforce another clause of the invaluable 14th Amendment. I quote Section 3: “No person shall… hold any office, civil or military, under the United States or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath… to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid and comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.” We should not ignore that last sentence. Former Confederates — like Solicitor General Conrad Holmes in United States v. Wong Kim Ark — were relieved of this disability as early as 1872, when Congress passed and President Grant signed the Amnesty Act that allowed former Confederates to return to active political life — and thus to participate in the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of Jim Crow.

Notes:

The transcript of United States v. Wong Kim Ark is available in Landmark Briefs and Argument of the Supreme Court of the United States, vol. 14, ed. Philip Kurland and Gerhard Casper (1975).

Amanda Frost’s 2021 book, You Are Not an American: Citizenship Stripping from Dred Scott to the Dreamers, in particular Chapter 3 “Birthright Citizen,” is a wonderful resource.

For a full account of the story of Chinese exclusion and the legal struggle of Wong Kim Ark, see Nackenkoff and Novkov, American by Birth: Wong Kim Ark and the Battle for Citizenship (2021).

For William Douglas O’Connor and his circle, including Walt Whitman, see (among others) Jerome Loving, Walt Whitman’s Champion (1978).

Really interesting (and so relevant), Crissy. (And how lucky you are to have such an estimable ancestor.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW and fascinating! Lynn

Sent from my iPad

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article! I especially like that you weave in your family history and current events. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! The more things change the more they stay the same.

LikeLiked by 1 person