On a Tuesday in early June 1944, near the end of 5th grade, I woke to find my mother extremely excited—almost speechless. She had been up for hours: my father was away, and my sisters and I were asleep. The phone had rung long before dawn, and in the days before caller ID and robocalls, you answered the phone when it rang—especially at an ungodly early hour, when it was likely to be an emergency.

On a Tuesday in early June 1944, near the end of 5th grade, I woke to find my mother extremely excited—almost speechless. She had been up for hours: my father was away, and my sisters and I were asleep. The phone had rung long before dawn, and in the days before caller ID and robocalls, you answered the phone when it rang—especially at an ungodly early hour, when it was likely to be an emergency.

It was an emergency. It was the New York Times, trying to reach one of their people—someone who lived in our apartment building, or perhaps was visiting there. The caller must have known my parents and where they lived; the Times wanted its missing person found and retrieved. The details are foggy; I’m not sure I ever really knew them, and I certainly don’t remember them now.  What I do remember is my mother’s excitement: she had been sitting with huge news, all by herself, for hours before she woke us. It was still too early for a newspaper, even for the special 6 a.m. edition of the June 6, 1944 Times—the one that went to press without the help of whoever was asleep in our building.

What I do remember is my mother’s excitement: she had been sitting with huge news, all by herself, for hours before she woke us. It was still too early for a newspaper, even for the special 6 a.m. edition of the June 6, 1944 Times—the one that went to press without the help of whoever was asleep in our building.

While writing posts for this blog, I have frequently wanted to kick my younger self. Why wasn’t I more alert and better-informed? Why didn’t I take an occasional note, or better still, keep a diary? Why didn’t I ask intelligent questions of those who are no longer available for interviews? I wish I had asked my mother who it was that the Times wanted to find—perhaps an expert on Normandy tides and beaches?—and why they had to use this rather random method to find him. (Note: I assume it was “him,” but I suspect that is a sexist assumption learned in the 1950s and not appropriate for the early 1940s, when women served as foreign correspondents overseas and as writers and editors in newsrooms at home, replacing men who had gone to war. Claudia Jones, for example, was Negro Affairs Editor at the Daily Worker in 1945 at the age of 30.)

Questions abound: even in 1944, long before writers and pundits and everyone else was accessible 24/7, wouldn’t the Times have had the phone number of someone they needed? They knew D-Day was imminent: everyone did.

Questions abound: even in 1944, long before writers and pundits and everyone else was accessible 24/7, wouldn’t the Times have had the phone number of someone they needed? They knew D-Day was imminent: everyone did.

The approaching 75th anniversary of June 6, 1944, sparked this flash of memory, and although I regret the loss of details, I can forgive my ten-year old self for neglecting to ask relevant questions.

What I cannot forgive is that this is also the one-year anniversary of an abysmal and embarrassing “mistake” by our so-called Department of State. On Tuesday, June 5, 2018, Heather Nauert, then the official spokesperson of our State Department, cited D-Day as evidence of the “very long history [and]… strong relationship with the government of Germany.” Ignorance and indifference are hallmarks of the Trump Administration, but for some reason—perhaps because I’m old enough to remember D-Day, if only in this idiosyncratic fashion—this particular instance of idiocy made me even more angry and sad than usual.

Nauert, who knows nothing of history or diplomacy, was shamed in the reality-based press for her “mistake,” but not by Fox News, where she got her “training.” PR work and right-wing journalism comprised the sum and substance of Nauert’s experience when she became our Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. As a co-anchor at “Fox and Friends” she followed the extremist Republican (sorry, redundant!) line down its nasty trail, calling undocumented immigrant children “illegals” and claiming they brought disease into the U.S. They are, of course, much more likely to become ill and even to die on our borders through neglect and mistreatment.

The Nauert story could have been worse. Not long after the D-Day fiasco, Trump nominated her to become our ambassador to the United Nations. She withdrew, not because of utter lack of qualifications, which is not a problem in the Age of Trump, but because of “nanny issues”—code for hiring undocumented employees, probably at below-market wages. Our ambassadors to the U.N. have, for the most part, been distinguished public servants: Adlai Stevenson, one of the early ones, must be turning over in his grave—or would be, if so many horrors were not competing to disturb his rest.

The Nauert story could have been worse. Not long after the D-Day fiasco, Trump nominated her to become our ambassador to the United Nations. She withdrew, not because of utter lack of qualifications, which is not a problem in the Age of Trump, but because of “nanny issues”—code for hiring undocumented employees, probably at below-market wages. Our ambassadors to the U.N. have, for the most part, been distinguished public servants: Adlai Stevenson, one of the early ones, must be turning over in his grave—or would be, if so many horrors were not competing to disturb his rest.

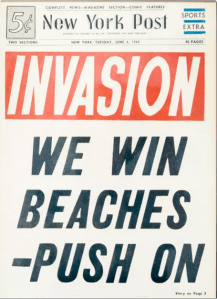

This post began as a slight, eccentric, but (for me) unforgettable glimpse of June 6, 1944—a child’s hazy memory of an impossibly long-ago time. I’m afraid it has become just another bitter reminder of what has happened to our country. In the course of thinking about D-Day, I looked at some old newspapers. The headlines and accompanying photographs reveal the breathless anticipation of what “we”—and there was a “we” then, at least on that day—expected would hasten the end of a devastating war. Desperate fear for the soldiers accompanied passionate hopes for victory and peace. It was long, long ago, and very unlike our own selfish and divided moment.

As celebrations of the 75th anniversary go forward this June, and the few survivors of the Normandy beaches gather to be honored, I’m going to conduct my own ceremony. I intend, if possible, to avoid thinking about the ignorant criminal in the White House and his hateful appointees for a full 24 hours. I’ll be remembering instead my mother’s breathless excitement, and the hushed anticipation of that distant day.

If you have D-Day memories I’d love to hear about them.

Pingback: #Tech #Support | The Oldest Vocation

I love the memory, the vivid child’s perspective. The clarity and specificity are such a contrast to the amorphous waves of idiocy that constitute “the news” these days.

Years ago I saw a program that asked young people on the street if they knew what the term “the Holocaust” referred to–and was stunned by the number who had no idea. A few knew it was linked to WWII, but that was as good as it got.

Some of those young people might be Trump supporters today, and it makes me wonder if we aren’t paying our national dues for failing to educate our citizens. Nauert is, among other things, the product of a failed system, or many many failed systems.

I wonder if we, as a nation, will ever have the will to place education of our children as a top priority.

As always, this essay is both touching and terrifying–and illuminating.

LikeLike

Thank you! I so much appreciate your thoughtful comments ..

LikeLike

Very moving, Crissy. My mother’s tears of joy (I was inside her at the time), came a couple of months later when the Allies entered Paris and she heard the Marseillaise on the radio (the wireless) for the first time in years

LikeLike

Thanks, Bartle – love your “memory!”

LikeLike

Splendid! Splendid! You needn’t fault yourself for not having been more observant on June 6, 1944. You were only 10 years old. I was 15 and I remember almost nothing – maybe the radio announcements.

At home we received only Il Progresso Italo-Americano. In the evening my mother would read aloud portions of it to my father who was illiterate. My mother’s village school went only to the 3rd grade.

For us the real war was in the Pacific where my brother Steve was flying missions with the USAF. That’s where the danger lay.

After the U.S. invaded North Africa, my brother Frank and I taunted my poor father: “Ora la Siciilia!” “Sicily is next!.”

“Solo con il binocolo,” he snorted. “Only with the spyglass.” He made a trombone-like gesture with his hands, spelling out a very long spyglass. But he was glad when Sicily was taken. Within weeks we received a letter from his brothers and sister in Sant’Anna.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this memory

of what was then called “the Home Front!”

LikeLike

Crissy, as always, your thoughts are illuminating and ask us to look at things in fresh ways. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading!

LikeLike