I was the mother of three in 1965, when it became legal for married couples in Connecticut to buy and use contraceptives. I didn’t live in Connecticut, luckily, but I welcomed news of the decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, the case in which SCOTUS established the right to privacy—another long stride, or so it seemed, in the march toward justice and freedom.

Those of us who came of age in the United States in the 1950s tended to believe, if only half consciously, in the idea of progress. Why wouldn’t we? Having grown up within the restraints and restrictions of the 1940s and 50s, we rejoiced as they relaxed and sometimes even disappeared during the next decades. Whether we watched from the sidelines or participated in the struggles for civil rights, for an end to the Vietnam War, for women’s rights and the freedom to choose, we were certainly aware that the times were a-changing. We changed too. My supposedly Silent Generation, especially those of us who were white and privileged, grew from youth into middle age during a vast, if uneven, expansion of rights and growth of freedom.

Although contraceptives were available outside of Massachusetts and Connecticut, abortion was neither legal nor readily accessible. With the necessary resources you could persuade two doctors, one of whom had to be a psychiatrist, to testify that you were not healthy or mentally stable enough to carry a child. Or you could go to Sweden, or some other sane country. For most women, however, the only option was an illegal and dangerous abortion. Many died and many more were injured, often in a manner that precluded future pregnancy. Some of these “women” were teenagers; some were impregnated by rapists, sometimes their own fathers. We know all this. We have known it forever, or what feels like forever to those who remember the panic-stricken wait for a late or missed period.

As I grew older I celebrated Griswold and Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey and happily assumed that my daughters and granddaughters would grow up free of state interference with their bodies. Now it looks as if they may not: what is happening now in Texas—and all too soon, probably, in much of the rest of the country—looks a lot like the 1950s. To make matters worse, some nasty twists of 21st-century cruelty, complete with vigilantes, have been thrown into the mix.

Half a century later, the very notion of progress is laughable. Our optimism has been eroded by catastrophic climate change, by the theft of voting rights for which our heroes suffered and died, by the blatant attempt to destroy democracy itself. As for reproductive rights, it seems that my granddaughters may have fewer than I did—and I didn’t have many, at least not during the part of my life when they would have been most useful. When I was in my teens and twenties, way back before the Pill, before second-wave feminism, before Roe and Casey, was there any acceptance of reproductive choice, let alone sexual freedom? Not in my world.

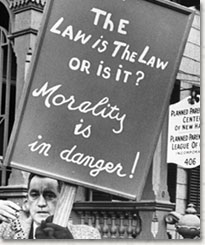

Lately I’ve been thinking about our lost sense of progress, recalling some of the events and decisions we celebrated as milestones—most recently the Griswold case, when the Supreme Court overruled Connecticut’s ban on the purchase and use of contraceptives. (I’m pleased to note that the notion of such a prohibition sounds far-fetched, even quaint, but that may not be true for long.) Griswold overturned the 19th-century Comstock Act, which had made illegal the “use (of) any drug, medicinal article, or instrument for the purpose of preventing conception.” Anthony Comstock, who gave his name to the infamous Act, was a postal inspector, Secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, and a zealot on the subject of “obscenity”—or really, any reference to sex. Anthony was particularly bothered by written materials that might go through the mail: the purpose of his Act was “The Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use.”

By the 1950s the Comstock Act remained on the books only in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and by 1965 it had been overtaken in both law and society. Several legal challenges to the Act preceded Griswold; in one of these (Poe v. Ullman, 1961), although the Court eventually refused to hear the case, the discussion provoked a significant dissent by Justice John Marshall Harlan. Harlan argued for an expansion of the constitutional concept of “liberty,” asserting that it is “not a series of isolated points (but) a rational continuum which… includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints.” At last!

A majority of the Court refused to rule on Poe, dismissing it as “theoretical” because the plaintiffs, clients of the Planned Parenthood League of Connecticut (PPLC), were not actually arrested or convicted. But PPLC persisted: they opened a clinic in New Haven in November 1961 with the express purpose of challenging the Comstock Act. The executive director, Estelle Griswold, was arrested along with the medical director, Dr. Lee Buxton. The two were tried, convicted, and fined $100 each, and when their convictions were upheld by the Connecticut Supreme Court, they appealed to SCOTUS. This time, the case was heard.

During my recent reflection on Griswold I had the good fortune to speak directly with an active participant, a client of PPLC who turned state’s evidence at the request of Estelle Griswold. The Reverend Joan Bates Forsberg was a minister and young mother in New Haven when, as she puts it, she “backed into” Griswold. She and her husband, also a minister, lived in a low-income section of the city; neither they nor their neighbors could afford private doctors. With three children and plans for further education, the Forsbergs wanted help with family planning. No such assistance was available to poor people in Connecticut, so Joan drove across the state line to the Planned Parenthood clinic in Port Chester, New York. Her neighbors sometimes inquired, teasing, about how she intended to avoid another pregnancy, and when they asked she told them about Planned Parenthood. Before very long she was taking van loads of friends along on her trips to the clinic in Port Chester, where a woman could be fitted for a diaphragm or prescribed the newly-available Pill.

None of this was available nearer home. Once, during a visit to Grace New Haven Hospital for a checkup, Forsberg overheard the doctor in the next cubicle advising his patient that she must not, for the sake of her health, become pregnant again. “Can you help me?” the woman said. The doctor said he could not; he simply repeated the warning. Most accounts of Griswold ignore this negative evidence of the impact of the Comstock Act. As I studied the case, I read again and again that the Act was “not enforced.” Not true: it was enforced, not by great numbers of arrests, but by discouraging clinics from opening and by preventing doctors in public hospitals from prescribing contraceptives or instructing patients in their use. As always, the most profound effects were felt by people of color, the young, and the poor.

When she heard the welcome news of a Planned Parenthood clinic in her own city of New Haven, Forsberg made an appointment during the first week it was open. After seeing a doctor and receiving a supply of pills, she thanked Estelle Griswold for her service to the community and offered “anything she could do” to help. “Anything” very quickly became a lot: the clinic was investigated by the police at the end of that week, and the director called Forsberg the next day. She and two other women were asked to report to the police that they had visited the clinic and received contraceptives, to turn over their medical records, and to testify at the trial of Griswold and Buxton. As Joan Forsberg recalls all this today, she says that one thing just led to another: as she tried to continue her education and take care of her family, she found herself first at the clinic, then the police station, then in court. “The worst part,” she told me, “was giving up her pills” [but she was able to get more!].

The case against PPLC and its directors moved through the Connecticut judicial system to the state supreme court, which upheld the Comstock ban on contraceptive purchase and use. The defendants appealed to SCOTUS, and in an historic 7-2 decision, the justices overturned the Connecticut courts. Their opinions are very much worth reading for their significance in later cases such as Roe and Casey, and certainly in the light of the present-day threat to abortion rights. Moreover, they are written with what looks now like a notable degree of attention to human reality as well as to the law and the facts of the case. That may not have seemed remarkable in the 1960s, but it’s a poignant reminder for anyone who heard our newest “Justice” opine that abortion is no longer necessary. (The recent oral arguments in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health can be found on the SCOTUS website for those who have the stomach for them. The Griswold opinions are available in many places, including the Library of Congress (PDF), and John W. Johnson, Griswold v. Connecticut: Birth Control and the Constitutional Right of Privacy, 2005. )

The significance of Griswold rests chiefly on its establishment of the right to privacy, which is not specified in the Constitution. Justice Douglas, writing for the majority, acknowledged this but asserted that a married couple is a free “association,” protected as such from interference by the state under the First Amendment and from “unreasonable search and seizure” by the Fourth. He made the case in vivid terms: “The prospects of police with warrants searching the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives is repulsive to the idea of privacy and of association…” Justice Arthur Goldberg concurred, arguing that the Ninth Amendment guarantees that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people,” and that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment promises that such “retained” rights cannot be infringed upon by the states. Goldberg described the right of privacy as rooted in “the traditions and collective conscience of our people.” He quoted Louis Brandeis, who had stated years before that the authors of the Bill of Rights “sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred… the right to be let alone.” (That last phrase, much borrowed, was originally used by Thomas Cooley, a Michigan judge writing on tort law in 1879.)

Griswold has had a long and significant afterlife, even—or especially—outside “the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms.” Not long after that momentous decision, the establishment of the right to privacy made it possible for unmarried couples and gay couples also to be let alone. And in 1973, the case served as an essential building block in Roe v. Wade, when – we believed—freedom of choice was finally established. The late Sarah Weddington, who at the age of 26 argued Roe in front of the Supreme Court, was interviewed in 2003, on the 30th anniversary of her successful litigation. She said then that she “had thought… that by this time… the controversy over abortion would have gradually faded away and we could go on to other issues. I was wrong.”

We were all wrong, and the picture has grown darker since 2003. When I talked to Joan Forsberg, we reminisced about a time when Griswold seemed to mark a crucial step in our advance toward a more just and humane future. Now, sadly, it is beginning to look like another disappearing milestone, vulnerable to the cruel and careless fascism of the United States in the 21st century.

Thank you, Thank you, Thank you! Excellent article. I can’t believe we are in this terrifying place. Never thought my daughter would be witnessing the stripping away of the right to an abortion in her lifetime. Abhorrent.

LikeLike

A wonderful essay and like all the work here, so informative. I really like Harlan’s assertion that the freedoms are not individual points but a spectrum that sweeps, rationally, practically, right to left including all territory between. No–that’s not exactly what he said, but it’s my version. One of the beauties of history, that Atkinson sees and shares, is that it’s full of such insights and reassurances. We’ve almost stopped expecting moving rhetoric or deep insight from any public figures–it seems too much to ask. We just want them not to be tragically stupid and crude and cruel. Also, Atkinson raises a crucial question–how far will this fear-based insanity go? All the way back to making contraceptives illegal? That’s a wake-up call. We are on the road to the past–though to a corrupted and even more dangerous version.

LikeLike

Thank you for this from France! I have students who will be interested to read this.

LikeLike

Let us in some way (by attachment electronically, by US Mail, by torch light from steeple to steeple) send Atkinson’s piece to ten friends, with the suggestion that they, in turn, send her piece to ten others.

LikeLike

Dear Crissy,

Such a powerful and thoughtful piece of writing! Thank you for this.

LikeLike

Methinks we’re returning to the Dark Age. Just a thought: if abortion is banned will they give free contraceptives to every man and woman who may be sexually active? Let’s take that to the Supreme Court as well.

LikeLike

Wow, Crissy. First-rate writing. Thank you. …Nancy

On Sun, Jan 9, 2022 at 5:27 PM The Oldest Vocation wrote:

> Clarissa Atkinson posted: ” I was the mother of three in 1965, when it > became legal for married couples in Connecticut to buy and use > contraceptives. I didn’t live in Connecticut, luckily, but I welcomed news > of the decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, the case in which SCOTUS esta” >

LikeLike