When I retired from academic life in the early 2000s I turned my attention from the Middle Ages to the 1950s, leaping over several centuries in a single bound. It was an uncomfortably long leap in lots of ways, but I was intrigued by the decade of my youth. I suspected there was more to it than I remembered, and more than was suggested by fifties stereotypes. I began by re-reading a few old novels with a new eye. (Does anyone remember Marjorie Morningstar? Goodbye, Columbus? It’s difficult to get through either one with a raised consciousness.) The magazines were enlightening, too – especially old New Yorker magazines and their cartoons.

This was all a lot of fun, but then I got serious and started looking for historical studies of the times, paying special attention to the Civil Rights movement; I remembered the excitement of the Brown decision, and – dimly – the Montgomery bus boycott. I was also curious about what had been going on, if anything, for women – surely someone before the 60s, before the women of SNCC or Betty Friedan, was aware that not all was as it should be. I browsed in the library and made a lucky hit on one of those rare books that forces you to change direction.

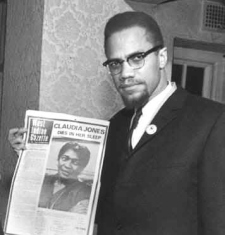

In Kate Weigand‘s Red Feminism: American Communism and the Making of Women’s Liberation (2001), I found someone so interesting that she stopped me in my tracks – Claudia Jones, whose short life (1915-64) included one stunning achievement after another. Jones actually wrote – in 1949! – about the relationship of gender to race and class. “Negro women – as workers, as Negroes, and as women – are the most oppressed stratum of the whole population.” Until I read Jones’s analysis of this triple oppression, I had believed that the relationship of race and class to gender – in the lingo of academic feminists, intersectionality – was discovered in the 1970’s and 80s by my cohort of second-wave feminists. Jones recognized it long ago.

In Kate Weigand‘s Red Feminism: American Communism and the Making of Women’s Liberation (2001), I found someone so interesting that she stopped me in my tracks – Claudia Jones, whose short life (1915-64) included one stunning achievement after another. Jones actually wrote – in 1949! – about the relationship of gender to race and class. “Negro women – as workers, as Negroes, and as women – are the most oppressed stratum of the whole population.” Until I read Jones’s analysis of this triple oppression, I had believed that the relationship of race and class to gender – in the lingo of academic feminists, intersectionality – was discovered in the 1970’s and 80s by my cohort of second-wave feminists. Jones recognized it long ago.

In order to understand the extraordinary career of Claudia Jones, I had first to find out much more than I had learned by simply living through the Cold War and the McCarthy era. Proximity in time was not much help, and neither was proximity in place: Jones lived and worked in New York City while I was growing up there, but I never heard of her. That’s not really surprising, all things considered, although now it seems dreadful that I could actually have heard her speak, but never did so. What is much more surprising, and horrifying, is that my ignorance persisted through the rest of the twentieth century, through all those years of work and study in feminism and civil rights. The silencing impact of the McCarthy years had, and has, a long half-life.

In order to understand the extraordinary career of Claudia Jones, I had first to find out much more than I had learned by simply living through the Cold War and the McCarthy era. Proximity in time was not much help, and neither was proximity in place: Jones lived and worked in New York City while I was growing up there, but I never heard of her. That’s not really surprising, all things considered, although now it seems dreadful that I could actually have heard her speak, but never did so. What is much more surprising, and horrifying, is that my ignorance persisted through the rest of the twentieth century, through all those years of work and study in feminism and civil rights. The silencing impact of the McCarthy years had, and has, a long half-life.

Very briefly, Claudia Jones was born Claudia Vera Cumberbatch in Trinidad in 1915: 2015 is her centenary year. She immigrated with her family to the United States at the age of eight, grew up in Harlem, and became a Communist in the late 30s. Smart, energetic, and a fine public speaker, she rose quickly within Party ranks as a writer, editor, and recruiter, and thus was targeted with other Party leaders during the McCarthy years. Jones was one of twelve prosecuted in the second show trial of Communists under the Smith Act, in 1953. She was arrested several times, spent almost a year in prison, and was finally deported to the United Kingdom in 1955. She lived the last decade of her life in London, where – finding British Communists indifferent or hostile to questions of race, and unenthusiastic about women leaders – she turned her attention elsewhere.

Jones landed in London in the middle of a surge of immigration to the UK from the islands of the West Indies and was quickly drawn into West Indian issues and affairs. She recognized and responded energetically to the familiar circumstances of virulent racism and disadvantage for people of color. Only three years after her arrival, Jones had become the founding editor of The West Indian Gazette, a monthly paper that was much more than a newspaper – in her capable hands, it turned into a primary organizing center of the Caribbean community.

Jones landed in London in the middle of a surge of immigration to the UK from the islands of the West Indies and was quickly drawn into West Indian issues and affairs. She recognized and responded energetically to the familiar circumstances of virulent racism and disadvantage for people of color. Only three years after her arrival, Jones had become the founding editor of The West Indian Gazette, a monthly paper that was much more than a newspaper – in her capable hands, it turned into a primary organizing center of the Caribbean community.

In 1958 there were race riots in London, following the murder of Kelso Cochrane, a young Antiguan carpenter. In the face of violence, and thanks to Claudia Jones, the West Indian community responded by staging the first of London’s Carnivals in 1959 – the huge and successful beginning of a tradition that continues today as the Notting Hill Carnival. The idea itself, as well as the organizing, came from Jones and the Gazette. The paper, broke as always, raised some money – but much more than that, the community had an opportunity to demonstrate, as Jones phrased it, “a pride in being West Indian.” She was sharply and profoundly aware of the relationship of politics and culture: as she wrote in the program of the first Carnival, “A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom.”

Claudia Jones died at Christmas, 1964. She was not yet fifty years old, but had suffered through her short life from the consequences of poverty in childhood and exhausting overwork till the end. She is buried next to Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery and remembered proudly and affectionately in her second adopted country, if – until recently – nearly forgotten in her first.

Claudia Jones died at Christmas, 1964. She was not yet fifty years old, but had suffered through her short life from the consequences of poverty in childhood and exhausting overwork till the end. She is buried next to Karl Marx in Highgate Cemetery and remembered proudly and affectionately in her second adopted country, if – until recently – nearly forgotten in her first.

As I did my research, one of the people I was fortunate to meet in London was Diane Langford, who – as she says, “through an accident of history” – became the custodian and guardian of Claudia Jones’s papers. Langford came to London from New Zealand in the 1960s and quickly got involved in all kinds of left-wing groups and activities. In the 1970s she was married to Abhimanyu (“Manu”) Manchanda, who had been Jones’s companion and colleague during her last years. When Manchanda died, Langford and their daughter, Claudia Manchanda, took over the care of Jones’s papers: most of these were sent to the Schomburg Center of the New York Public Library in 2001. Now Langford has launched Abhimanyu Manchanda Remembered, which includes letters between Jones and Manchanda. The material itself has been deposited in the Marx Memorial Library in London. (See also Langford’s notes on Jones and Manchanda.) Many of Jones’s papers were lost when she died; what remains – and indeed, much of what we know about her – we owe to Langford’s devoted attention.

Jones’s writings, which were scattered in many places when I began my work (see below), are now collected in Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment (2011), edited by Carole Boyce Davies. American historians have begun to pay attention to Jones and other radical women, especially African American women, in the national and international politics of the Cold War: see especially Carole Boyce Davies (Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones), Erik S. McDuffie (Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism), and Dayo F. Gore (Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War).

In the long run, after several years of attention to Claudia Jones, what I found most compelling was the story of her experience and achievements in the UK. With barely enough money to live on, abruptly deprived of friends, family, and employment – how could she possibly have accomplished what she did? I never answered that question – it still astonishes me – but I thought about it constantly as I read her newspaper, walked in her footsteps in London as well as New York, spoke with some of those who knew her, and left flowers at the small stone that lies at Highgate in the shadow of the huge bust of Karl Marx.

In the long run, after several years of attention to Claudia Jones, what I found most compelling was the story of her experience and achievements in the UK. With barely enough money to live on, abruptly deprived of friends, family, and employment – how could she possibly have accomplished what she did? I never answered that question – it still astonishes me – but I thought about it constantly as I read her newspaper, walked in her footsteps in London as well as New York, spoke with some of those who knew her, and left flowers at the small stone that lies at Highgate in the shadow of the huge bust of Karl Marx.

It has been an extraordinary privilege to discover Claudia Jones. Stumbling over her was like falling into an enormous, unexplored room in a house you thought you knew. When I worked in medieval history, I expected everything to be foreign and strange, but this was the 1950s – I was there – and so was Claudia Jones. If I had known!

I take this opportunity to post here two earlier pieces from my work on Claudia Jones: A Strange and Terrible Sight in Our Country, a 2006 essay based on a letter Jones wrote from detention on Ellis Island in 1950, originally published in The Women’s Review of Books, and “A Pride in Being West Indian”: Claudia Jones and the West Indian Gazette, an unpublished paper written in 2012.

Finally, I dedicate this post to the memory of Jean Hardisty, who admired and respected Claudia Jones as much as I do. Jean not only gave advice and encouragement, she loved this blog, and never said “Can’t you put this in a book?

Update 4/27/17

I recently had occasion to remember an archival treasure I came across in connection with my research on Claudia Jones, regarding her dear friend Benjamin Davis, here:

Pingback: P.S. “A Strange and Terrible Sight” | The Oldest Vocation

Pingback: D-Day Memory: Then and Now | The Oldest Vocation

Pingback: “I Question America” | The Oldest Vocation

Pingback: P.S. “Not used in Bulletin. Put in file.” (1956) | The Oldest Vocation

Pingback: Coming of Age in the 1950s All Over Again | The Oldest Vocation

Oh my,

I’m sorry and ashamed to say I did NOT know her – but it is a thrill to make her acquaintance! So many important voices have been repressed/suppressed/oppressed. (If only we had known about and proceeded along the path of Jones’ thoughts on intersectionality starting back in the 50’s, we would be farther along on our long march to freedom.) But Jones story is one that does not DEpress – a Carnival as a revolutionary response to racist violence – how fabulous is that! It was also a thrill to see this dedicated to Jean Hardisty, whose voice continues to call us to conscience.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Crissy, for sending this to me. You are right: I do like–and admire and appreciate–Claudia Jones. I apologize for asking wasn’t there a book here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perfectly OK! and thanks for reading. . .

LikeLike

Once again, Atkinson adds to our one-dimensional notion of this rich era, which seems to continue to be represented in the larger culture by a slender blonde wearing a delightful apron. Claudia Jones is the answer to that lie, the woman who spoke and wrote and edited and went to jail and saw and recorded every flaw in the system. History will serve us all much better with women like this–both Jones and Atkinson–made visible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is wonderful — stunning information about a person few of us knew about, shared so appreciatively and politically astutely. If I can figure out how, I am going to share this widely — particularly with progressive women of color.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m sure you’ve read it, but David Halberstam’s “The Fifties” is a wonderful history of the decade, including his insights from having been a young reporter in the South for part of the decade.

LikeLike

No wonder you were so long silent. This is wonderful… How fitting to have finally connected with Jones by placing a flower on her tomb. That memory lives long after the flower withered – and it propagates: it belongs to me and to everyone who will read your blog. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Wonderful article, Crissy. You are right; Jean would have been thrilled with one more article about Claudia. What an amazing woman Claudia was.

LikeLiked by 2 people

lovely and moving. I too am sorry I missed Claudia Jones.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great piece! As always, you reveal a hidden part of our history and bring it to life. Claudia Jones, yes.

LikeLiked by 2 people